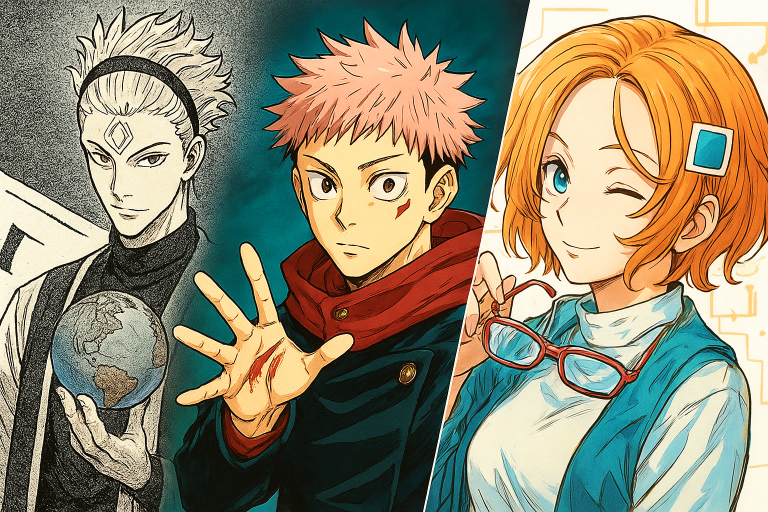

The arrival of Jujutsu Kaisen Season 3, titled The Culling Game Part 1, has set the anime community ablaze, not just for its high-octane action but for its incredibly dense and artistic opening sequence. Set to the catchy song “Aizo” by King Gnu, the visuals are a departure from previous seasons, opting for a deeply symbolic and historical art-driven approach.

MAPPA has “cooked” a visual feast that blends classical Western art, Japanese block prints, and cryptic manga foreshadowing. Here is a comprehensive breakdown of the art references and story secrets hidden in plain sight.

More Information: Jujutsu Kaisen Season 3: Culling Game Arc Part 1 — Worldwide Schedule, Episode Release Timings & More

Jujutsu Kaisen Season 3: Culling Game Part 1 Opening:

Art References in the Jujutsu Kaisen Season 3 Opening

The opening masterfully uses world-famous paintings to mirror the tragic and complex relationships within the series.

1. Egon Schiele’s Dead Mother

One of the most unsettling references in the opening draws from Egon Schiele’s Dead Mother, a painting born from emotional absence rather than comfort. Schiele’s original portrays motherhood as hollow and suffocating, stripping the womb of warmth and turning it into a space of quiet dread.

That idea is reimagined in Jujutsu Kaisen through Yuji Itadori, shown enclosed within the body of Kaori Itadori—who, at this point, is no longer truly his mother. Her form is already claimed by the ancient sorcerer Kenjaku. The womb, usually a symbol of protection and origin, becomes something closer to a prison. Yuji is not being born into the world; he is being prepared for it. This image reframes his existence as something engineered rather than nurtured, suggesting that his fate was sealed long before he ever took his first breath.

2. Peter Paul Rubens’ Two Sleeping Children:

The opening briefly shows Mai and Maki Zenin asleep together as infants, a rare image of peace before their lives were shaped by cruelty. This moment references Two Sleeping Children (1612–1613) by Peter Paul Rubens, a melancholic painting of orphaned siblings that balances innocence with quiet tragedy.

In Jujutsu Kaisen, the parallel cuts deeper. Before cursed energy, clan expectations, and resentment defined them, Mai and Maki were simply sisters—equal, protected, and untouched by judgment. The still captures a version of their bond that was never allowed to exist for long. The Zenin clan’s ideology would soon poison that innocence, making this calm feel less like a memory and more like a stolen future.

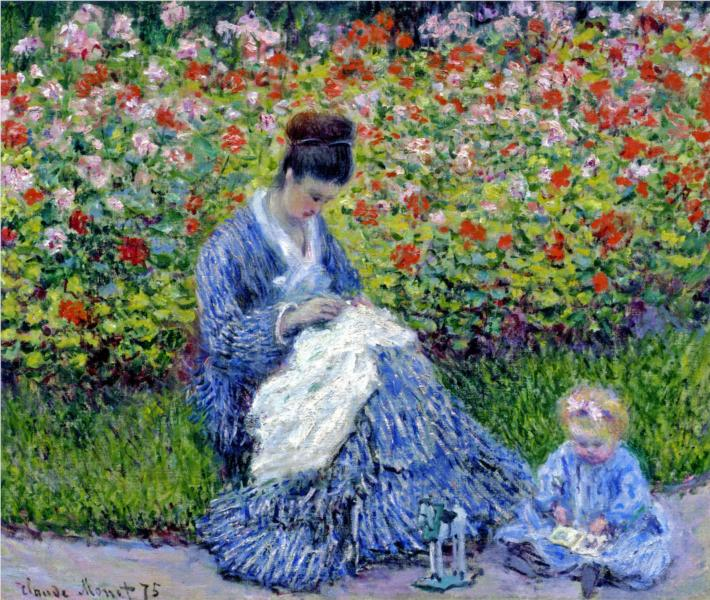

3. Claude Monet’s Camille Monet and a Child:

Panda and Masamichi Yaga are framed in a soft, impressionist-inspired scene reminiscent of Claude Monet’s Camille Monet and a Child, an image overflowing with warmth that feels almost out of place in Jujutsu Kaisen. The reference highlights something the series rarely allows to exist peacefully: found family. Panda may be a cursed creation, but this moment quietly affirms that he is still someone’s child, and Yaga is unmistakably his father.

Yet the tenderness of the scene carries an unspoken tension. Much like Monet’s original—painted shortly before personal tragedy—the calm feels temporary. Jujutsu Kaisen never shows peace without consequence, and this gentle image subtly foreshadows the cost Yaga will soon pay. It’s a reminder that even the purest bonds in this world are never spared for long.

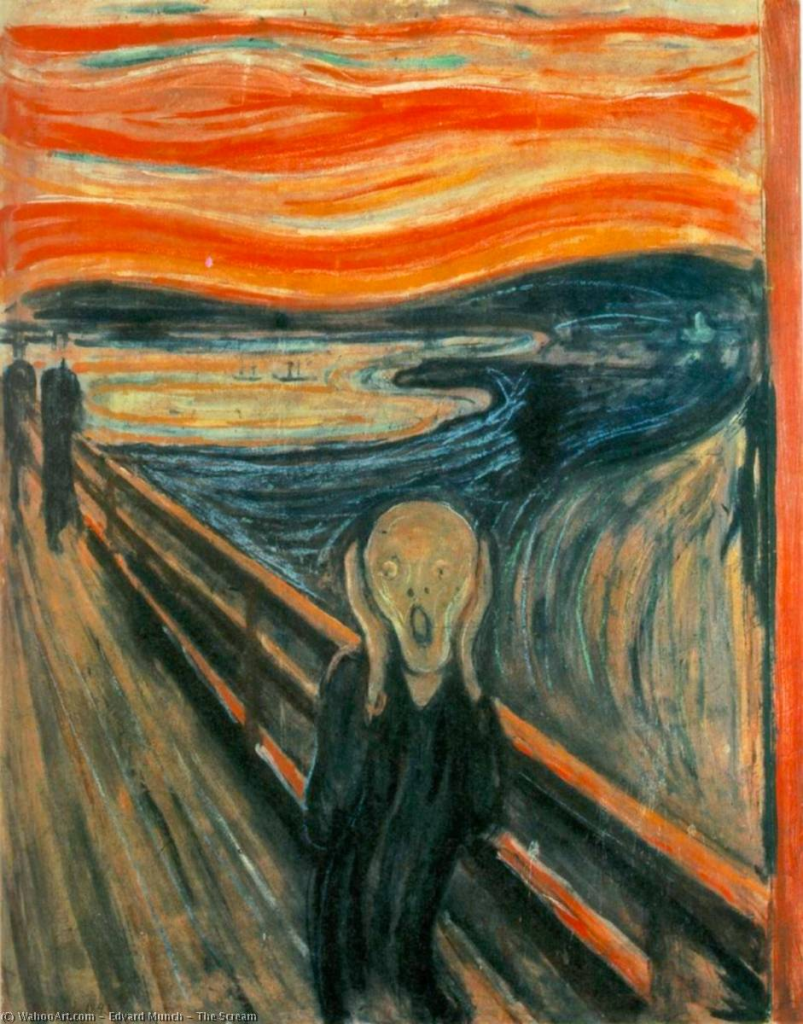

4. Edvard Munch’s The Scream:

The opening also invokes Edvard Munch’s The Scream, using its distorted horror to embody the Zenin twins’ mother. The warped face and suffocating panic reflect a woman crushed by fear, resentment, and helplessness, emotions she ultimately passed on through neglect and emotional abuse. This image directly echoes the Perfect Preparation arc, where Maki Zenin is forced to confront her mother not as a parent, but as a broken product of the Zenin clan itself.

Beyond the individual, the reference works as a tonal warning for the Culling Game. Like Munch’s figure, the characters are pushed beyond endurance, screaming without sound as the world demands more cursed energy, more sacrifice, and more suffering. It captures a core truth of Jujutsu Kaisen: terror is not theatrical—it is internal, corrosive, and inescapable.

5. John Everett Millais’ Ophelia:

Mai Zenin is framed drifting in water, surrounded by flowers, a direct visual echo of John Everett Millais’ Ophelia. In the original painting, Ophelia’s calm surface masks a mind already broken, her surrender to the water feeling less like a choice and more like an inevitability. That same unsettling stillness defines Mai here. The lake is quiet, almost beautiful, but it carries the weight of something already decided.

Within Jujutsu Kaisen, this image becomes a quiet premonition. Mai’s expression isn’t fear or resistance—it’s acceptance. The flowers floating around her symbolize innocence and grief, but also finality. This is not a moment of tragedy in motion; it is the moment before it. The opening frames Mai’s fate exactly as the series treats sacrifice: not as a heroic climax, but as a silent exchange—her life, given willingly, so Maki can finally break free from their cursed lineage.

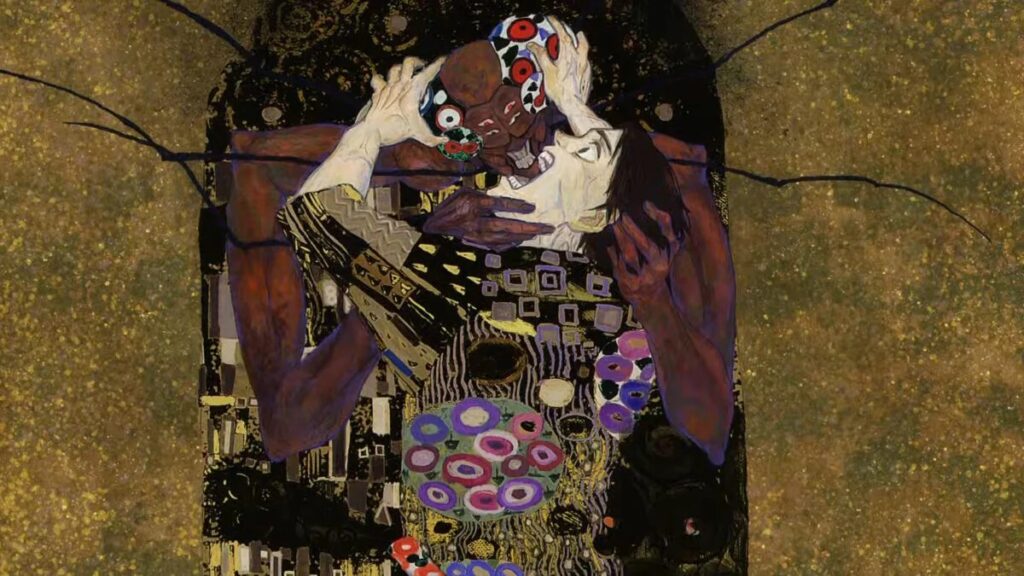

6. Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss:

One of the opening’s most unexpected references draws from Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss, reimagined through Yuta Okkotsu’s encounter with Kurourushi, the Special Grade cursed spirit. At a glance, the pose feels almost playful, a rare moment of levity amid the opening’s emotional heaviness. This shot is often misinterpreted as an intimate callback to Yuta and Rika, but that reading is deliberately misleading. The opening is not romanticizing their bond—it is subverting it. Manga readers immediately recognize the irony behind the image.

In Klimt’s original, the kiss represents eternal devotion and unity. Here, that intimacy is intentionally distorted. The closeness between Yuta and Kurourushi precedes not affection, but annihilation. What reads as humor on the surface doubles as a reminder of Yuta’s terrifying composure: even tenderness becomes a weapon in his hands. Within the Culling Game, beauty and brutality are inseparable, and death often arrives wearing a smile.

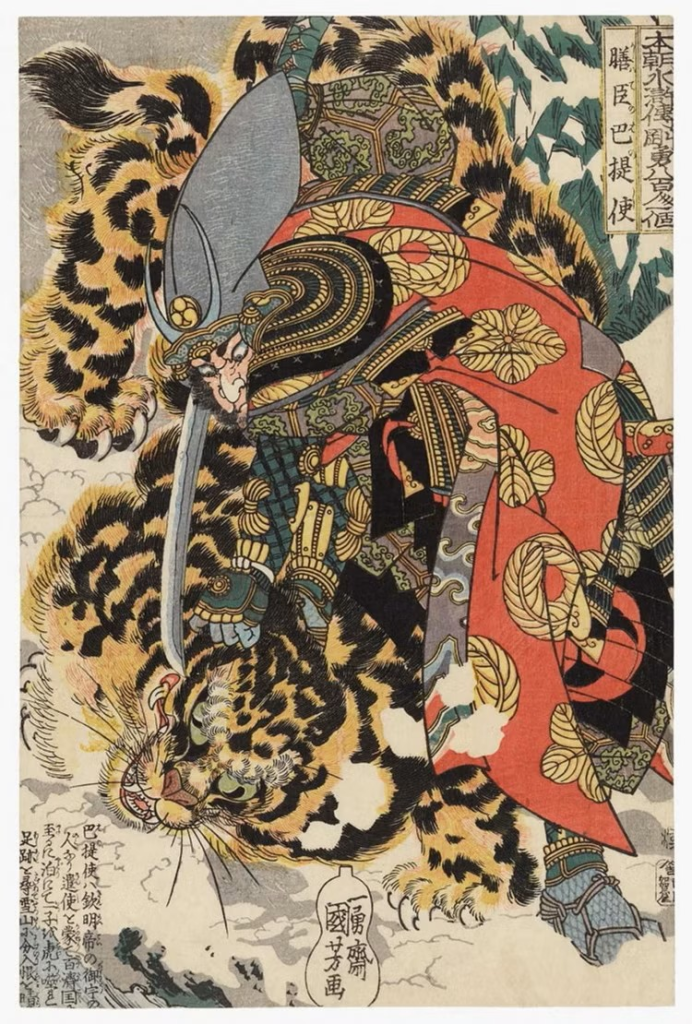

7. Kashiwadi no Hanashi: Eight Hundred Heroes

Maki Zenin is shown poised to strike down a tiger, a direct reference to Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s Kashiwade no Hanashi from the Eight Hundred Heroes series. In the original woodblock print, a man kills a tiger in vengeance for his child’s death—an act driven by grief, rage, and an unyielding will to challenge something far stronger than himself. That same defiance defines Maki’s journey.

The tiger becomes a stand-in for the Zenin clan, an embodiment of oppressive tradition and inherited cruelty. Maki’s stance reflects not just physical strength, but revenge, liberation, and a refusal to remain prey. With the introduction of Naoya Zenin early in Season 3, the opening quietly foreshadows an inevitable clash. This is not a heroic pose—it is a declaration of war.

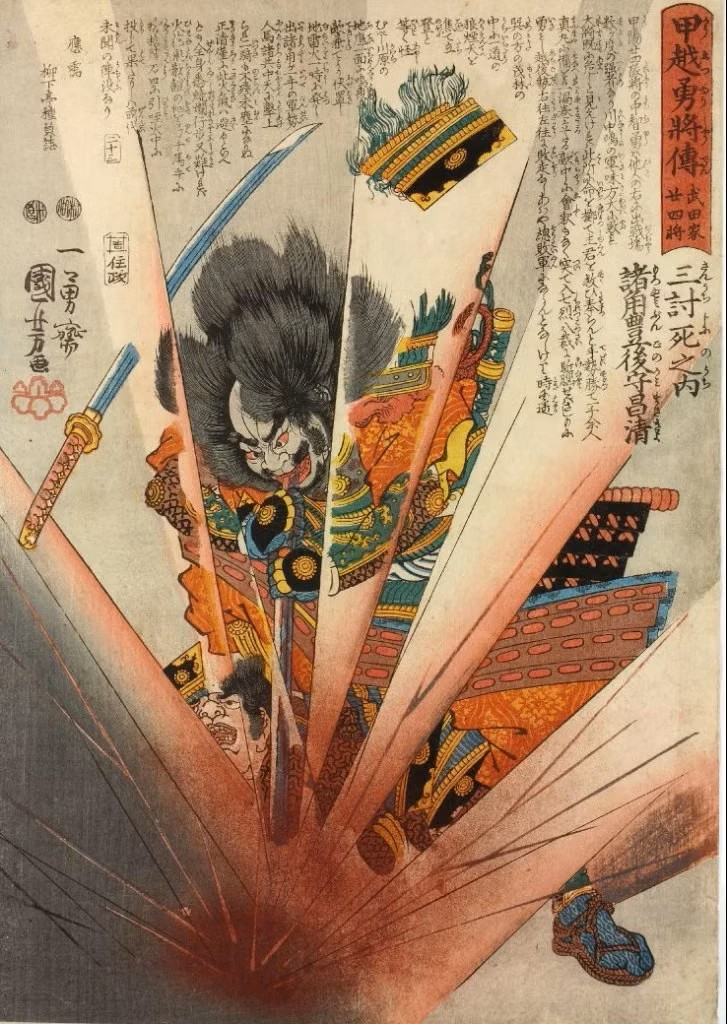

8. Morozumi Bungo-no-kami Masakiyo, One of Three Heroic Deaths in Battle

Yuta’s moment in the opening goes by fast, but it hits like a loaded reference if you catch it. The pose recalls Kuniyoshi’s battle prints, specifically works like Morozumi Bungo-no-kami Masakiyo from One of Three Heroic Deaths in Battle, where a lone warrior brings down a monstrous serpent through sheer resolve. Strength here isn’t elegant—it’s overwhelming, almost reckless.

What makes this shot interesting is how many directions it points at once. On the surface, Yuta mirrors the classic image of a hero slaying something far larger than himself, echoing pieces like Wada Heita Tanenaga Killing a Huge Python. But there’s another layer fans immediately latch onto: the resemblance to Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre, with Mahoraga visually standing in for the impossible, inhuman threat. The enemy is too big. That’s the point.

9. “Y-Junctions” by Tadanori Yokoo

The opening briefly lingers on a stark Y-shaped intersection, a visual pulled from Tadanori Yokoo’s Y-Junctions series. Unlike the grand tragedies referenced elsewhere, this image feels strangely ordinary. Yokoo originally used these junctions as a way of revisiting his hometown, filtering familiar roads through memory rather than meaning. And that’s exactly why the reference works.

In Jujutsu Kaisen, the fork in the road doesn’t promise destiny or heroism—it offers uncertainty. The Culling Game doesn’t ask the characters to choose the right path, only to choose something. Every option carries loss, and hesitation is just another way to fall behind. The opening reinforces this by showing figures from behind, faceless and unresolved, as if even the story itself refuses to tell us who will walk which road. It’s a reminder that from here on, survival isn’t about conviction—it’s about living with whatever choice you make.

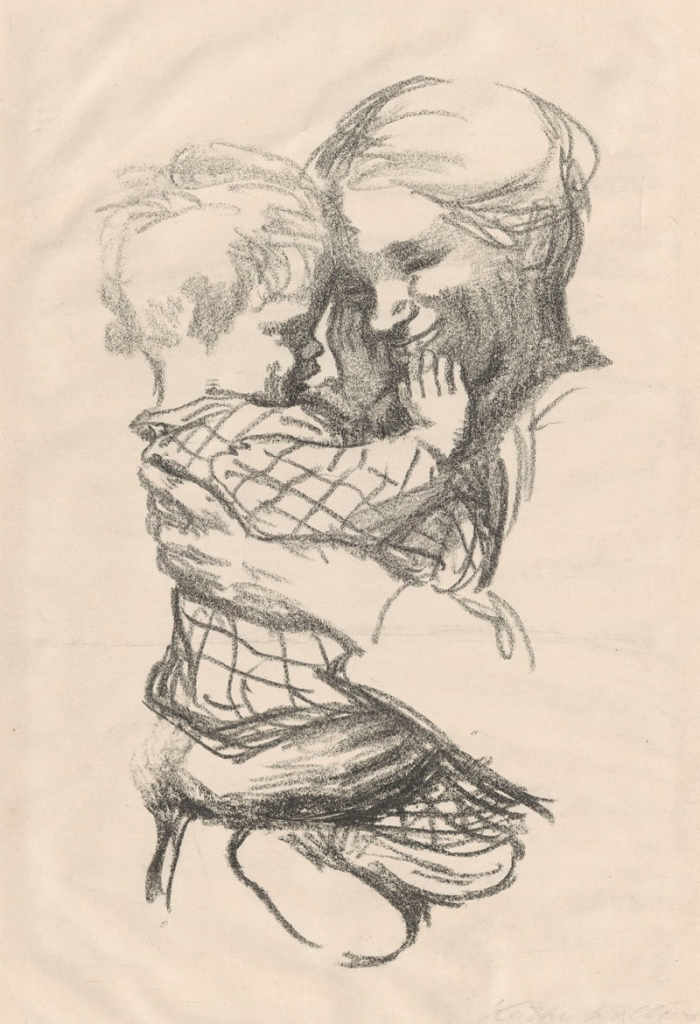

10. Käthe Kollwitz's Mother with a Child in her Arms

One of the most subdued references in the opening draws from Käthe Kollwitz’s Mother with a Child in Her Arms, a work defined not by spectacle, but by weight. The drawing is raw and heavy, centered on a mother clutching her child with a desperation that feels less protective and more fearful—like she already knows what the world intends to take.

As per the latest fan theories, this image is reflected through Kusakabe’s sister and her son, Takeru. There’s no action here, no looming threat in the frame, and that’s precisely what makes it unsettling. Kollwitz’s art has always been about quiet suffering, about civilians and families crushed beneath forces they never chose to confront. By invoking it, the opening reminds us of what the Culling Game truly endangers—not just sorcerers and curses, but ordinary lives caught too close to the fallout.

Additional Hidden References in the Jujutsu Kaisen Opening

1. Ghost in the Shell: Standalone Complex

There’s a moment in the opening where the sorcerers stand together in rigid formation, and it immediately triggers déjà vu. The composition mirrors the iconic opening pose from Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex, a visual shorthand long used in anime to signal that the story is entering dangerous territory. When characters line up like this, it’s never for show—it means something irreversible is about to begin.

In Jujutsu Kaisen, the reference carries the same weight. This isn’t camaraderie or bravado; it’s resolve. The group isn’t preparing for a battle they expect to win cleanly—they’re bracing themselves to hold the line, to protect Master Tengen from Kenjaku, no matter the cost. By invoking such a recognizable anime image, the opening quietly tells the viewer: the rules have changed. From here on, every move matters, and not everyone standing here is guaranteed to walk away.

2. Pink Floyd's Dark Side of the Moon

The opening sneaks in two very different pop-culture references almost back-to-back, and the contrast feels intentional. Hakari’s introduction channels Tyler Durden from Fight Club—all loose confidence, swagger, and controlled chaos. It frames him as someone who thrives in instability, the kind of person who treats violence and risk like a game he’s already solved.

Right after that, the tone shifts completely with a flash of imagery inspired by The Dark Side of the Moon, tied to Takako Uro. The prism, the fractured light, the sense of reality bending at the edges—it mirrors Uro’s Sky Manipulation, where space itself becomes unreliable. Direction warps, surfaces break, and the sky turns into something she can fold, shatter, and weaponize. Space bends and light lies.

3. Kenjaku Keeping an eye on Yuji Itadori

The opening begins with Kenjaku watching Yuji Itadori, framed not as an enemy, but as an observer. The angle places him above, distant and composed, like a scientist studying an experiment rather than a villain confronting a hero. Yuji isn’t being targeted—he’s being monitored.

As the sequence continues, Kenjaku’s gaze expands over Japan itself, reinforcing his role as the architect of the Culling Game. What makes the imagery unsettling is its calmness. While friendships form, and brief moments of normalcy flicker by, Kenjaku remains unblinking, patiently watching his design unfold. The opening makes one thing clear: this isn’t chaos spiraling out of control—it’s a controlled experiment, and Yuji stands at its center.

Final Thoughts

The first opening of JJK Season 3 isn’t just something you watch once and skip—it’s something you revisit, frame by frame. I’ve done my best to cover every major art reference, symbolism, and hidden detail woven into it, but knowing Jujutsu Kaisen, there’s always more lurking beneath the surface.

If you caught a reference I didn’t mention, let me know in the comments. The Culling Game has only just begun, and this opening is already telling us more than it should.

Related Articles:

- Jujutsu Kaisen Season 3: Culling Game Arc Part 1 Premieres Jan 8, 2026 — Timings and Worldwide Schedule

- Jujutsu Kaisen Season 3: Culling Game Arc Official Trailer, Phantom Parade Game & JJK Execution Movie

- Jujutsu Kaisen Creator Gege Akutami Returns With New Manga Starting Sept 8

- Ultimate Guide to Jujutsu Kaisen

- The Most Awaited Anime of 2026 (So Far)

- 50 Most Underrated Anime — The Best Recs You’ll Ever Get!

- Fall 2025 Anime Guide: 15 Shows Every Otaku Needs on Their Watchlist

- Top 10 Anime Fights with God-Tier Animation

Good read. Love the insight. You are missing one of the references: The three judges.

what a good read! Thank you for your effort in finding all these references, one more reason to love JJK

Great site you’ve got here.. It’s hard to find excellent

writing like yours nowadays. I truly appreciate individuals like you!

Take care!!